View associated photo essay featuring over 100 period photographs: http://www.pinstripepress.net/CWDrummerBoys.pdf

Throughout the history of warfare musicians have always played an important role on the battlefield. Military music has served many purposes including marching-cadences, bugle-calls and funeral dirges. Fifes, bagpipes and trumpets are just some of the instruments that were used to instruct friend and intimidate foe.

Perhaps the most notable of these instruments was the drum. From as far back as the ancient days of Babylon, the beating of animal skins rallied the troops on the field, sent signals between the masses, and scared the enemy half to death. During the Revolutionary War, drummers in both the Continental and English ranks marched bravely into the fight with nothing but their sticks to protect them.

Remarkably, some of these musicians were in fact, very young boys, not quite yet into their teen years. That group however, was a minority. Despite popular culture’s portrayal of the little “Drummer Boy,” boys were actually an acceptation to the rule in early American warfare. According to The Music of the Army… An Abbreviated Study of the Ages of Musicians in the Continental Army by John U. Rees (Originally published in The Brigade Dispatch Vol. XXIV, No. 4, Autumn 1993, 2-8.):

Boy musicians, while they did exist, were the exception rather than the rule. Though it seems the idea of a multitude of early teenage or pre-teenage musicians in the Continental Army is a false one, the legend has some basis in fact. There were young musicians who served with the army. Fifer John Piatt of the 1st New Jersey Regiment was ten years old at the time of his first service in 1776, while Lamb’s Artillery Regiment Drummer Benjamin Peck was ten years old at the time of his 1780 enlistment. There were also a number of musicians who were twelve, thirteen, or fourteen years old when they first served as musicians with the army.

Sixteen years, although young by today’s standards, was considered the mature age of a young man in the days of the American Revolution. It was also the average age of many fifers and drummers who volunteered to march in the ranks of General George Washington’s Continental Army. For example the 11th Pennsylvania Regiment boasted the following musician’s roll:

John Brown, fife – 14 years old, enlisted in 1777 (11 years in 1777) Thomas Cunningham, drum – 18 years old, enlisted in 1777 (15 years in 1777) Benjamin Jeffries, drum – 15 years old, enlisted in 1777 (12 years in 1777) Robert Hunter, drum – 40 years old, enlisted in 1777 (37 years in 1777) Thomas Harrington, drum – 14 years old, enlisted in 1777 (11 years in 1777) Samuel Nightlinger, drum – 16 years old, enlisted in 1777 (13 years in 1777) James Raddock, fife – 16 years old, enlisted in 1777 (13 years in 1777) George Shively, fife – 19 years old, enlisted in 1777 (16 years in 1777) David Williams, drum – 17 years old, enlisted in 1777 (14 years in 1777)

Despite their non-combatant roles in battle, many of these drummer’s war stories are even more compelling than those of the fighting men around them. For instance, Charles Hulet, a drummer in the 1st New Jersey…The following deposition was given by Hulett’s son-in-law in 1845:

“… said Hulett… enlisted in Captain Nichols company [possibly Noah Nichols, captain in Stevens’ Artillery Battalion as of November 9, 1776. In 1778 he was a captain in the 2nd Continental Artillery. See entry for Joseph Lummis] which was a part of the first Regiment of New Jersey in the service of the United States which Regiment was commanded by Col. Ogden. He enlisted as aforesaid on the 7 May 1778… He was engaged in the battle of Monmouth and was wounded in the leg and then or soon after taken a prisoner and by the enemy and carried in captivity to the West Indies, To relieve himself from the horrors of his imprisonment he joined the British Army as a musician and was sent to the United States. That soon after his return… he deserted from the British ranks and again joined the army of the United States and the south under General Greene. He was present at the siege of York and after the surrender of Cornwallis he was one of the corps that escorted the prisoners which was sent to Winchester… and he remained in service to the end of the war. This declarant always understood that said Hulett at the close of the war held the rank of Drum-Major.”

As primarily noncombatants, it is rare to have a detailed look at the service of any military musician. John George is an exception to that rule as he served the Continental Army’s supreme commander as his personal percussionist. His descendants have also done an exceptional job keeping his legacy alive through public commemorations. Arville L. Funk’s study titled From a Sketchbook of Indiana History, includes a profile of the first “famous” American drummer. It reads:

In a little known grave in south-western Marion County, Indiana, lie the remains of an old soldier traditionally acclaimed as “George Washington’s drummer boy.” This is the grave of Sergeant John George, a Revolutionary War veteran of the First Battalion of the New Jersey Continental Line. Through extensive and alert research by Chester Swift of Indianapolis into Revolutionary war records, muster rolls, field reports, pension records, etc., there is evidence that Sergeant George might have been the personal drummer boy of Washington’s Headquarters Guard during a large portion of the Revolutionary War…On September 8th of that year, Private George, who was listed on the company’s rolls as a drummer, fought in his first battle, a short engagement at Clay Creek, which was a prelude to the important Battle of Brandywine. Later, Ogden’s battalion was to participate in the battles of Germantown and Monmouth, serving as a part of the famous Maxwell Brigade. The Maxwell Brigade served during the entire war under the personal command of General Washington and was considered to be one of the elite units of the American army. According to John George’s service records, he served his first three-year enlistment as a private and a drummer with the brigade at a salary of $7.30 a month. When his three-year enlistment expired, George reenlisted as a sergeant in Captain Aaron Ogden’s company of the First Battalion (Maxwell’s Brigade) for the duration of the war.

Drummer boys during the American Civil War were younger than their predecessors, but more advanced in their playing. Each drummer was required to play variations of the 26 rudiments. The rudiment that meant attack was a long roll. The rudiment for assembly was (777 flam flam 777 flam flam 777 flam flam 77 flam flam 7) and the rudiments for the drummers call was (7 flam flam 7 flam flam 7 flam flam 2x fast, 1x slow 7 flam 7 flam). The rudiment for simple cadence was (open beating) (55 flam flam repeat). Additional requirements included the double stroke roll, paradiddles, flamadiddles, flam accents, flamacues, ruffs, single and double drags, ratamacues, and sextuplets.

Many drummers learned how to play by attending the Schools of Practice at Governor’s Island, New York Harbor, and Newport Barracks, Kentucky, although the vast majority learned in the field. Some were aided by texts; the most popular by far was Bruce and Emmett’s The Drummers’ and Fifers’ Guide.

According to historian Ron Engleman:

The word rudiments first appeard in a drum book in 1812. On page 3 of A New Useful and Complete System of Drum Beating, Charles Stewart Ashworth wrote, Rudiments for Drum Beating in General. Under this heading he inscribed and named 26 patterns required of drummers by contemporary British and American armies and militias. The word Rudiment was not used again in US drum manuals until 1862. George B. Bruce began page 4 of Bruce and Emmett’s Drummers and Fifers Guide with the words Rudimental Principles.

Beginning with the long roll, Bruce listed 35 patterns concluding with a paragraph titled Recapitulation of the Preceeding Rolls and Beats. On page 7 of his 1869 Drum and Fife Instructor, Gardiner A. Strube wrote, The Rudimental Principles of Drum – Beating, and followed with 25 examples, each named Lesson.

Military drums were usually 18” or more prior to the Civil War when they were shortened to 12”-14” deep and 16” in diameter in order to accommodate younger (and shorter) drummers. Ropes were joined all around the drum and were manually tightened to create tension that stiffened the drum head, making it playable. The drums were hung low from leather straps necessitating the use of traditional grip. Regulation drumsticks were usually made from Rosewood and were 16”-17” in length. Ornamental paintings were very common for Civil War drums which often depicted pictures like Union eagles and Confederate shields.

The younger the drummer the more difficulty one would have lugging around these cumbersome instruments. However, that aspect didn’t deter boys from taking up the instrument. According to a brief history on Civil War drummers:

Although there were usually official age limits, these were often ignored; the youngest boys were sometimes treated as mascots by the adult soldiers. The life of a drummer boy appeared rather glamorous and as a result, boys would sometimes run away from home to enlist. Other boys may have been the sons or orphans of soldiers serving in the same unit. The image of a small child in the midst of battle was seen as deeply poignant by 19th-century artists, and idealized boy drummers were frequently depicted in paintings, sculpture and poetry. Often drummer boys were the subject of early photographic portraits.

The youngest soldier killed during the entire American Civil War (1861–1865) was a thirteen year-old drummer boy named Charles King. He had enlisted as a drummer boy in the 49th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry with the reluctant permission of his father. On September 17, 1862 at the Battle of Antietam he was mortally wounded near or in the area of the East Woods, carried from the battlefield to a nearby field hospital where he died three days later.

Twelve-year-old Union drummer boy William Black was the youngest recorded person wounded in battle during the American Civil War. One of the most famous drummers was John Clem, who had unofficially joined a Union Army regiment at the age of nine as a drummer and mascot. Young “Johnny” became famous as the “The Drummer Boy of Chickamauga” where he is said to have played a long roll and shot a Confederate officer who had demanded his surrender.

On the southern side an 11-year-old drummer in the Confederate Kentucky Orphan Brigade, known only as “Little Oirish,” was credited with rallying troops at the Battle of Shiloh by taking up the regimental colors at a critical moment and signaling the reassembly of the line of battle.

Another noted drummer boy was Louis Edward Rafield of the 21st Alabama Infantry, Co. K, known as the “Mobile Cadets.” He had enlisted at age 11 and while 12 at the Battle of Shiloh he somehow lost his drum; he then obtained an enemy drum and kept on going, thus earning the title of “The Drummer Boy of Shiloh.”

As the years passed the drum was eventually replaced on the battlefield in favor of the bugle although it often returned during Veteran Reunions that took place decades after the war. Many drummers had gone on to become drum majors or drum instructors themselves.

One notable post-war percussionist was Alexander Howard Johnson, the drummer boy of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry made famous by the film Glory. Johnson was said to be a talented drummer who served with distinction and later became s sought after instructor. According to Johnson, he continued to play the drums all his life.

Four years after the South’s surrender Johnson organized “Johnson’s Drum Corps.” where he led the band as drum major, and styled himself as “The Major.” According to a local writer who interviewed Johnson years later.

He is probably one of the best drummers in Massachusetts, and boasts that there is hardly a drummer who marches the streets of Worcester who has not received instruction from him.

No one can dispute the service of the drummer boy who left the safety of their homes and firesides to serve their respective cause in a man’s war. It is unfortunate that their contribution is so often overlooked. Their legacy lives on. Today America’s armed forces boast some of the most talented musicians in the country with many of them still playing traditional instruments and cadences. Military drummers are still highly respected and carry on the tradition of their instrument’s storied history that should not be forgotten.

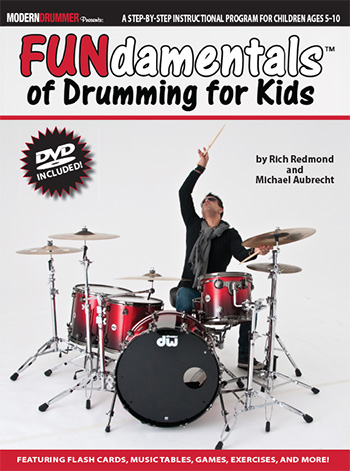

About the author: Michael Aubrecht is a drum and Civil War historian whose books include The Civil War in Spotsylvania, Historic Churches of Fredericksburg and FUNdamentals of Drumming for Kids which he co-wrote with Rich Redmond. Visit him online at https://maubrecht.wordpress.com/.