Heavy Metal Hero

Heavy Metal Hero

by Michael Aubrecht

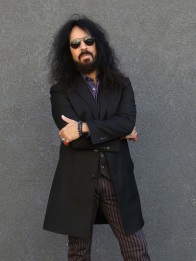

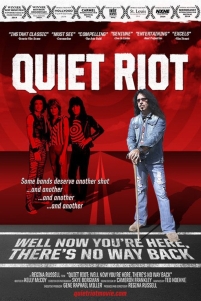

Not many bands from the 1980’s can boast the level of success that Quiet Riot can. No other band from the metal genre bridged the gap between hard rock and mainstream music. With catchy songs, tongue-in-cheek videos and stellar musicianship Quiet Riot set the bar for hard rock acts everywhere. Their debut album “Metal Health” hit the top of the Billboard charts, making it the first heavy metal album to go #1. Laying down the foundation for the band was a rock-solid drummer named Frankie Banali. Obviously influenced by John Bonham, Banali’s ability to create an infectious groove gave Quiet Riot a distinctive sound. Later in his career Banali stepped away from the band to play with WASP, another highly original heavy metal act. He also played with punk-pop phenomenon Billy Idol and was the touring drummer for Faster Pussycat, Australian Billy Thorpe and classic rock icons Steppenwolf. In recent years Regina (Russell) Banali produced a critically-acclaimed documentary on the trials and tribulations of reforming Quiet Riot titled “Well Now You’re Here, There’s No Way Back.”

The first concert I ever attended was Quiet Riot in Pittsburgh on their “Condition Critical Tour.” Although I was only in the seventh grade, I vividly recall the experience like it was yesterday. What I recall most was Banali’s massive black and white striped drum kit. At the time it was the coolest thing I had ever seen. As a budding drummer I was hypnotized by the sheer magnitude of the 360 degree kit that surrounded Banali. I was especially drawn to the double bass setup with the octabans and rack toms up front. (My first kit was a white Pearl Export and I seriously thought about grabbing some electrical tape and striping it myself.) Banali was a great showman who was not eclipsed by his kit. Like most drummers today, Banali has stripped down to a standard five piece in place of his signature monstrosity. Even with the minimal kit, his huge booming sound remains. Banali was my first drum hero and he is directly responsible for me being a drummer today. I thank him for that.

Despite having a rotating line-up, Banali remains as the band’s drummer and manager. Thanks to his dedication and effort Quiet Riot is still rocking out to whole new generation of fans. Their mix of classics and originals satisfy loyal fans from the past and inspire new fans for the future. Very few bands have that kind of staying power. All along Banali’s leadership has maintained the band’s foundation on the stage and off. Far more than just a drummer, he is a musician’s musician. That is why he is still considered to be one of the best from the classic metal genre. A huge thrill for me, Frankie took time in between gigs to discuss his experiences from yesterday to today.

MA: First off, congratulations on debuting your new singer James Durbin. I’ve read some very positive reviews online. People are really responding to your shows.

FB: Thank you. It felt great.

MA: I know part of this story but please enlighten our readers. What brought you to the drums?

FB: Even when I was a little kid I was drawn to the instrument. I was told by my parents that I used to pull the pots and pans out of the cupboards and start beating them with a wooden spoon. I think it was preordained because I have no real recollection of doing that. I do remember the first snare drum that I made. I took a coffee can and a piece of paper and put the paper on top of the can with a rubber band around it. Then I took every pen that was in the house and undid the little springs. I attached the springs to the bottom of the can to get a snare drum sound. There was always music in my parent’s house. Neither of my parents were musicians but they loved music. My father loved big band swing music, jazz and opera. My mother really enjoyed flamenco music. My father was born in Italy and my mother was born in Spain. Their backgrounds influenced the music we had in the house. The first three records my father gave me was a Buddy Rich big band record, not a solo album but one he performed with other musicians, a Max Roach record and a Miles Davis record. I still have all three. It all started from that. I think the reason my drum sound developed the way it did was because I got used to hearing big, loud, drums. Back in that period the big band drummers were using 24-26”even 28” bass drums. They were generally mic’d with just a single microphone so that big ambient sound was something that I was already in tune with. This was years before the similar rock and roll drum sound. Eventually I developed an appreciation for the tighter Bebop sound of the “new era” jazz via Miles Davis, Max Roach, Tony Williams etc.

MA: That makes sense as the drummers from the big band era had to project their sound beyond the bandstand and out onto the dance floor. That inspired the hard-hitting drummers that were to come.

FB: Another thing that I noticed early on was the tuning range of the drum set. Listening to all of the drummers from that era I picked up on the fact that drummers had to be tuned in between the horns and the bass. In other words, their sound had to sit right in the middle between the high and low instruments. That knowledge came to me well before I saw The Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show. My parents watched Ed Sullivan religiously every Sunday after dinner. I remember sitting there on the floor in front of the TV watching The Beatles and that was the moment that shifted what I had been listening to – to what I became obsessed with. Rock and Roll took over all of my attention. Ringo, later on Charlie Watts and Dave Clark became my main influences. Those were the drummers that taught me how to play songs. Not just drums but the whole song. Being a musician first and a drummer second. They showed me how to practice restraint and add the punctuations at the right time. To this day, they directly influenced what I bring to the table and what I have tried to do my entire career. I much prefer to play a song than a drum solo. The next change after that happened as soon as Cream came out, and Jimi Hendrix, end especially Led Zeppelin. As soon as Zeppelin released that first album in 1969 I never looked back.

MA: I heard in another interview that you made a deal with your dad to get drums.

FB: Yes. Before I discovered my love for drums I was very active playing hockey. I was a goalie and it was my whole world. I also played baseball. I was into sports. As soon as I became interested in drums that all ended. I literally put down the hockey stick and picked up the drumsticks, but I kept the baseball bat behind the front door… My father thought it was going to be some passing thing. He didn’t want to invest in something that was going to end up rotting in the basement. He told me that if I took lessons for a year he would buy me a real drum set. I got my 3F sticks and went to the DeBellis School of Music in Astoria Queens New York. I took lessons there from a drummer named Ernie Grace who supposedly was the drummer at one time with The Deuce of Dixieland. I took lessons for a year. The first song I ever learned to play was Bill Haley and The Comet’s “Rock Around the Clock.” I learned that tune inside and out, beat for beat. It was kind of out of sight out of mind for my father, but after a year of weekly lessons I went up to him and reminded him that it was time to buy me drums. I literarily had my hands out ready to collect. We went back to DeBellis which was also a music store. I wanted a Ludwig drum set just like Ringo had. I wanted the black oyster pearl finish. My dad was really big about buying New York made products so he bought me a blue-sparkle Kent drum set. It was OK, and it was my first. A year later I finally got my Ludwig in red sparkle. It was a 22,” 13,”16” and a 5×14” snare.

MA: Nice. Did you participate in any music programs at your school?

FB: Yes I did. When I was going to school there were two things that I did. One was the Navy Scouts which was a naval version of the Boy Scouts. I played in their marching band. I also took music lessons in school but they already had too many drummers so the music teacher gave me a coronet. When I was a kid I suffered from chronic asthma. At one point I hit a C-note on that coronet and turned blue and passed out. I ended up in the hospital in an oxygen tent for several weeks. When I finally came back to school they took away the horn and gave me a pair of drumsticks. I guess it was meant to be. The great thing about that was the fact that I didn’t only have to learn rudiments. I got to play the kit and timpani as well. It was a perfect introduction to percussion instruments as a whole. That skill set has stuck with me for all of these years. I own more percussion instruments than drum sets. Even as a teenager I had two timpani and seven gongs ranging from 10” to 38” most of which I still own along with the two timpani and my drums. That was directly from my exposure to those instruments in school. No question that it made me a well-rounded musician. Glenn Hughes had a piece in Modern Drummer magazine in which he discussed the drummers that had worked with him. I was one of those drummers. He said that I stuck out because I was a very “musical drummer” who was just as much a percussionist as a drum set player. It was very complimentary. I wish I still had the copy [laughs].

MA: You have said that your main influences were John Bonham and Buddy Rich. How did each drummer’s distinctive style affect how you play?

FB: I believe that Buddy Rich is the greatest drummer ever to pick up drumsticks. I’m also a huge Tony Williams fan. I like Max Roach and Joe Morello. They are all amazing but there was something very special about Buddy’s interpretation and attitude. He represented things to aspire to although I would never be able to play most of the things that he did. It was his approach to the drums and how he listened to the other instruments, the accents that he did and the attack that he played with. His drum sound was booming. When you get to a guy like John Bonham you find something that is very interesting to me. Fortunately or unfortunately, I look at it as a positive. I’ve been around so long that I was old enough to understand the concept of The Beatles when they came out. By the time Led Zeppelin came out I was already in the fast lane. The reason why I say that is that I got to see Led Zeppelin in 1969. It was the last two shows that they did on the first leg of their first American tour. I didn’t have a car or a license obviously so my father drove me to the club, bought me a ticket and sat in our Cadillac with a thermos of espresso, the New York Times and a box of cigars. When I went into the venue, it was a club called Thee Image, I noticed that the drum set that John Bonham was using was the exact kit that I had been playing for almost a year. The reason I say this, and definitely not implying that I was ahead of Bonham, but at the time we must have been both listening to Carmine Appice when he was in Vanilla Fudge. We were obviously copping his look.

I was working two jobs after school. During the week I worked in a record store and on the weekends I worked part-time in a factory. With the money I had saved from that I ordered another drum set. It was a Ludwig kit with two 26” kick drums, 15” rack tom, 16” and 18” floor toms all in maple. When I saw John Bonham playing that drum set I said to myself I must be on to something here. Of course his playing was monstrous. It was interesting that when he did his drum solo, which was before he did Moby Dick, I immediately noticed that he was copping Max Roach. I think his approach with the hand playing was more Joe Morello than anyone else. Bonham’s approach playing bare handed was very much in the style of Morello which was deliberate, not whimsical like previous drummers like Papa Jo Jones approached it. Bonham pulled the sound out of the drums.

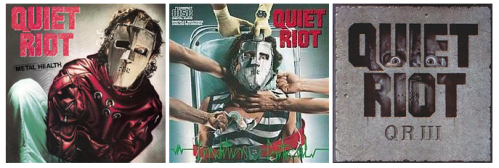

MA: While we are talking about sound, you have always has a very distinct sound. Listening to the first three Quiet Riot records (“Metal Health,” “Condition Critical,” “QR III”), it is impossible to miss the booming snare sound. In fact, the entire drum kit sounds huge. How did you accomplish this?

FB: In regards to your question about the snare. I used a 1975 Ludwig 6.5×14” Supraphonic Snare which I still own and record with. It’s retired from touring but I did use it as my main snare on the “Metal Health” and “Condition Critical” tours. I used a 1976 version as a back-up. I still own both of those drums. The last time I recorded with the ’75 was on one of the tracks on the forthcoming album. For the drums, on the first record I used a kit I had bought back in 1969. It was a Ludwig 26” bass, 15” rack, 16” and 18” floor toms. I occasionally substituted a second 14” rack tom but very rarely then, more so now. In order to get that sound took some work. I had been listening to many jazz drummers and their tuning range. Most drummers when they have big oversized drums tend to tune them lower in order to achieve what they think is a big sound. I always pitched mine up more than most rock drummers did. I tuned the bottom heads a third up from the top heads. That gave them projection. With drums the size that I just quoted, you can get a good response if they are tuned properly. I use no padding whatsoever. I used a single felt strip on the front of the bass drum and I mounted a microphone wrapped in foam inside of it from around 1978 to 1982.

A lot of people think that the “Metal Health” record was recorded in a big room but it wasn’t. At Pasha Studios the room was very small. Live is not what you can say about it. The bottom half of all of the walls were covered in shag carpeting. It had a drop-down ceiling of acoustical tile. When I first put my drum set in there I hated the sound. Actually that was before I ever recorded with Quiet Riot. I had done session work for Pasha prior to that. I manipulated the room around the drums. First I “acquired” some sheets of plywood from a construction site and lined all of the walls in the studio. The panels covered the carpet and allowed for a reflective sound. Then I took all of the acoustical tiles from above the drums. That allowed me to raise microphones higher into the ceiling. It was all a matter of tuning and adjusting the room to produce the sound that I heard in my head.

MA: It sounds like you were very meticulous. You must have had a good relationship with the engineer to allow you to take over. He wasn’t threatened?

FB: I would come into the studio two hours early in order to do this. I know that engineers are creatures of habit. Whatever works for them they tend to repeat over-and-over. Fully knowing this and not wanting a “cookie-cutter” approach I took it upon myself to create the sound I wanted. You have to remember that by the time I did the “Metal Health” record I had already played on a hit which was Billy Idol’s “Mony-Mony.” Because of that I knew my way around the studios. I also knew the psychology of working with producers and engineers and other musicians. What I would do is go in early and set everything up so when the engineer walked into the room and looked around I could sit down and play the kit, essentially proving that my adjustments made sense. It cut out the argument and the discussion of whether I could or could not try it out. It was proof positive.

MA: I’m surprised that you used such a small drum set in the studio when the kits you used live were enormous. Obviously this had a lot to do with show but I fondly remember your set-ups. The black and white striped drum set is probably my all-time favorite kit of any player. Did you have a favorite out of all the configurations that you used?

FB: How all of that came about was that the “Metal Health” record and the “Condition Critical” record were both recorded on five piece drum sets. “Metal Health” was done with my green-sparkle 1969 Ludwig kit and “Condition Critical” was done using a Pearl set as I had gotten an endorsement with them. The touring kits came about as Kevin (Dubrow) pointed out that we had to compete with all of these other bands. He recommended that I play a huge drum set. I didn’t have a problem with it. When I was younger I looked at Ginger Baker and Keith Moon and that led me to double bass kits with multiple toms and cymbals. When I was a teenager these set-ups had two 22” bass drums, three 13” racks and two 16” floor toms. I was confident that I could work my way around a large kit. Once I got the endorsement with Pearl I literally ordered the catalog and they were kind enough to send it to me. When we did the video for the song “Metal Health,” which was actually done before “Cum On Feel The Noize” and was released first, I didn’t have a big kit to play. In my storage locker I had a couple Slingerland bass drums, two North toms, and a couple extra floor toms. So the kit that you see in the video is actually a Frankienstein drum set that was put together with unmatched pieces. Of course that was never used live. That started the development of the big kits for me. By the time we were huge and after the “Condition Critical” album Pearl was happy to send whatever I needed. They were very-very good to me.

MA: You guys had a theme with stripes, the drums, the clothes, the guitars and the mic stands. How did that become prominent with the band’s style?

FB: It actually happened by coincidence. When I saw Kevin playing in the first version of Quiet Riot he already had the striped mic stand and was wearing striped outfits. I didn’t really pivot from him. If you go back and look at the promo pictures when I was touring with Steppenwolf on the road I was already wearing black and white striped tops. We were just on the same wavelength in regards to the look and it was a natural progression. If we were all wearing stripes, why not have a striped drum set?

MA: If I recall correctly didn’t you eventually integrate Simmons electronic pads into your set-up?

FB: That just happened. Simmons got in touch with me and wanted to send me a set to practice with at home. Back in the first version it was like playing on a Formica countertop. They had great bounce but they were terrible on the wrists and elbows. Once we got big and did long shows I had to do the obligatory drum solo. Because of my background in percussion I had a lot of options. I had the big kit, octobans out front, timpani, gongs and electronic pads. I mounted the Simmons above me on an angle. Another thing that I did was to prepare for unseen incidents. I had a DW trigger pedal next to my bass drum pedal. To the left of my snare drum I had another pad. I had my studio kick and snare sampled and assigned to the pads in case I needed to switch. That way if I ever broke a head I could continue playing seamlessly for the rest of the show.

MA: A lot of Quiet Riot’s songs begin with drum parts. Was that by design or did it happen naturally in the studio?

FB: To me it’s like a race car. Somebody sets the pace for the others to follow. I was the one who usually set the pace. The interesting thing about one of my more famous intros “Cum On Feel The Noize” was that it was not supposed to be on the record. The producer wanted us to record it. I didn’t care one way or the other but Kevin despised the song. I was aware of the song’s originator Slade but they were not the type of band that I would have listened to. Kevin did not want to do a song that had been written and recorded by someone else. We all came up with the idea that we would tell the producer that we were working on that song although we never did. The inevitable day came when we actually had to record it and in theory it was supposed to be an intentional train wreck. We wanted to make it so the producer couldn’t even use it if he wanted to. There we are in the studio looking at each other and there was some arguing. I went into the engineering room and told him that we hadn’t worked on the song and that we were going to tank it. I said that he might want to record it to be funny. He said OK. The producer comes in. There is no intro. If you listen to our version of the song it doesn’t start in the same place as the original. I actually forgot a verse or chorus that does not exist in our version. I started playing that drum beat and the others joined in. Kevin of course was waiting for it to fall apart but we just kept playing. It’s in my DNA to do the best job I can so I vamped and it turned out to work within the song. When we finished playing the producer said it sounded great on the first take. The engineer happened to record it and when we listened to it back it worked. Kevin on the other hand was furious.

MA: One of the consistent things that I find across all of these songs, especially the ones you intro, is how tasteful you play. You create these solid pockets for the rest of the band to follow and then splash in these great fills that punctuate the song. My favorite, “Condition Critical” starts out with a solid two and four beat and then has these lightning fast rolls down the toms. Your intro the “The Wild and The Young” is brilliant. How did you come up what that?

FB: Again that was a song that didn’t originally have a drum into. One day I was sitting in the room thinking about how I could get a different kind of sound that would retain the tight snare and kick drum but have different toms. I wanted to create something that was completely different. I had been experimenting with the engineer and ultimately we decided to set up four concert toms, a 12”and 13”on top and a 14” and a 15” on the bottom. We used shotgun mics aimed to the absolute center of the head and that produced a great sound. The sound is more about the attack and less about the tone. That dictated where I could get away with a very staccato and non-linear approach. The result is the intro on the record.

MA: In the video I recognize a lot of the pieces of your kits strewn about. There is literally a wall of drums behind you as you play. Are those all yours?

FB: Yes, every one of them. Nothing was rented [laughs].

MA: Quiet Riot managed to bridge the gap between metal and mainstream. At what point did you realize the impact the band was having on the music scene?

FB: We didn’t come out as gangbusters. It actually took about seven months from when the record was released to when it went #1. It was a struggle because everything was New-Wave and the Punk movement was still hanging around. When you consider that by the time we found out that we were #1 on Billboard we were a supporting act on the Black Sabbath “Born Again” tour. It was an amazing experience but at the same time we didn’t have the time to celebrate because we had an obligation as a supporting act. What really impacted me was the competition that we were up against. I mean we dethroned Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” which is considered to be one of the greatest albums of all time. We also beat the Police and Lionel Richie and Paul McCartney. There was nobody on Billboard that was even close to what we were doing. We were really carrying the banner for American metal music. Consequently what happened was we went gold, then platinum. The record companies pay attention to the financial value of an artist. They stood up and noticed Quiet Riot. This resulted in tons of bands being signed. Some good. Some not-so good. That’s the way business is. I have always held the contention that not only was Quiet Riot incredibly fortunate, but I was blessed to be a part of it. I feel a sense of accomplishment for the genre as we were the ones that opened up doors for so many other bands. That said, I never take credit for those bands being successful after they were signed because that happened, or didn’t happen, on their own merit.

MA: You guys were trend setters.

FB: There is no doubt that we were setting an example for what was possible. If you just look at it from a statistical point of view, look at November of 1983 when there was no American heavy metal on the charts. We defined it.

MA: Your fan base, the people that discovered you back in 1983, have stuck with you for decades. What do you attribute this longevity to?

FB: For me personally I’ve never taken the fans for granted. They are responsible for any success that we’ve had. I’ve never believed that once the fans make you, it’s OK to forget them. Their original support back in the day, to years and years later, to today is something that I hold very dear. As soon as I finish playing a show I don’t run backstage, I go to the fans at the front line so I can interact with them one-on-one. Giving someone an autograph, or taking picture, or just chatting shows people that you really care. Some bands never get close to their fans. I enjoy it. These people have given me the life that I lead. I will never take that for granted because I know a lot of my friends, some of them better musicians than I am, never had the opportunities that I’ve had. You never forget why you’re here.

MA: Speaking of “stars” you played drums on the Hear-n-Aid “We Are Stars” project to help promote famine relief in Africa. What was that like?

FB: I was one of two drummers, myself and Vinny Appice. I got a call from Jimmy Bain and Vivian Campbell. They told me about this idea that they were working on and if I would play drums on it along with Vinny. I consider that I was in DIO for one day [laughs]. It was Vivian Campbell on guitar, Jimmy Bain on bass, Vinny Appice on drums and Ronnie James Dio on vocals. Of course I said I’d do it. They came over to my house and played me an acoustic demo. Quite a few months passed before anything happened and I got the call to do the track. They had a firm date and couldn’t change it. It happened to fall on the day I got back from a South American tour with Quiet Riot so I literally got home from South America and went straight to the studio. It was an exhausting but wonderful experience.

MA: What an honor. Think of all the drummers that they could have chosen and they selected you.

FB: It was incredibly flattering and I love those guys. The great thing about it is when you listen to the track it doesn’t sound like two drummers. It sounds like one big drummer. We both blended together seamlessly. It was a lot of fun to do. I remember when we were working on it there is a section where we trade fours at the end. I fondly remember that we would come to that point and we would trade four-after-four-after-four. Finally Ronnie came running in the room screaming “Are you two ever going to stop!” It was definitely a highlight in my career.

MA: Beyond Quiet Riot you have played with other bands such as WASP, Faster Pussycat, Steppenwolf and Billy Idol. What was it like playing for Billy?

FB: The whole thing with Billy Idol was interesting how it came about. His producer had heard that I was a solid drummer, I was no nonsense, I was a quick learner and I showed up on time and was professional. Ultimately he heard that I got the job done quickly. I got hired to do the session. I met Billy for the first time and he was really intelligent, quirky and humorous. We talked about films. When it came time to do the session it took 45 minutes to get the drum sound and it took me half an hour to cut the track. They wanted to know if I wanted to record some more and I only had enough time to do one more song as I was double booked that day. I did one more tune and then I literally packed up my gear and went to another studio to work on some production demos for an artist named JC Crowley. All that in one day. Being a session drummer is hard work. You have to go to the artist, they don’t come to you. At one point when I was couch surfing in LA I realized that the only way I could support myself was to play in as many bands as I could. Generally speaking I was usually in no less than five bands at a time. I still have all of my schedule calendar books all the way back to ’78 or ’79. When I look back at all of those entries I am still amazed at how busy I was. I have a real strong work-ethic that I got from my father.

One of the greatest experiences of my life happened after my parents and I moved from New York to Florida. I was in a lot of local bands in the Ft. Lauderdale area and I was working at a record store called Sid’s Records and Tapes. That was a fun job for a musician like me. There was a fella by the name of Lou Dickstein who worked for Concerts West. At the time in the ‘70s they were the biggest concert promoters out there on the east coast. I had met him because the record store was a ticket vendor for them and I used to get into a lot of concerts for free. One day he came in and said Listen. I’ve got a show at Pirates World which was an outdoor venue. The opening band that he had scheduled backed out so he asked me if I could put my three-piece together and take their place. Of course I said “Sure!” Next thing I knew I found myself in my unsigned trio, who played half originals and half covers, opening up a show for David Bowie on the “Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars” tour. I was only nineteen or twenty at the time.

MA: What a memory, especially at such a young age. So I am guessing that these types of experiences gave you an understanding of the business that benefitted you as you got older.

FB: Yes I guess you can say that I became the complete package. By the time I had gone from the east coast, first to Chicago and then eventually to LA, I had a lot of experience. After doing that Bowie show we opened up for a band called Wishbone Ash at the Miami/Hollywood Sportatourium which is another big outdoor venue where I also saw Led Zeppelin play. There was a guy named John Peal who had a record called “The Pope Smokes Dope” which was produced by John Lennon. I think he started out as a street musician. My trio backed him. So I already had large audience experience and a sense of how to behave as a support act versus the headliner. The other key thing for me, that I was not prepared for and didn’t realize until I came out to LA, is that on the east coast you are used to playing six sets a night, forty-five minutes each, covering a wide variety of styles. That was the best training I ever had. On the west coast they played one thirty minute set and ran off the stage before you could work up a sweat. It was different but I quickly adapted so yes, I had a lot of experience when I actually came into the business at the higher level.

MA: I want to make sure we have some time to talk about your DVD “Well Now You’re Here, There’s No Way Back.” The film has been critically acclaimed and has even won some awards. It shows all the issues of reforming a band, some good moments, some not-so good moments. Were you nervous about being so transparent?

MA: I want to make sure we have some time to talk about your DVD “Well Now You’re Here, There’s No Way Back.” The film has been critically acclaimed and has even won some awards. It shows all the issues of reforming a band, some good moments, some not-so good moments. Were you nervous about being so transparent?

FB: No. Not exactly. How the whole situation came about was the director Regina Russell and I had a conversation and I told her that I was thinking about putting the band back together. Understanding the history of the band and knowing that I possess all of the band’s archives she thought we could put together something worthwhile. I had started managing the band back in 1993 and I kept everything so she knew she would have a lot of material to work with. She was also interested in the story of the band continuing on after the death of a bigger than life personality in Kevin Dubrow. It went from there but all the credit for the film goes to her. I’ve said it time and time again that I lived it. I did not make the movie. As a matter of fact, early on in the process I stopped watching any of the footage that was done because I was just too busy trying to keep Quiet Riot afloat in the midst of so much criticism and negative opinions about me continuing the band. I really didn’t pay much attention to the film at that point. I also didn’t want it to be some kind of sugar-coated white wash version of the truth. If you’re going to make a movie then have it be real. So I stepped away from it. There are things in there that make me uncomfortable or that make me cringe. I know that even the scenes I don’t enjoy were crucial to telling the whole story.

MA: Is it true that when you were on the fence about restarting the band you went to Kevin’s mother to get her blessing?

FB: Yes. Listen, I’ve been criticized by people who believe that I turned my back on a statement that I would not carry on. I think it is important to understand that for twenty-seven years every time I stepped on a stage it was Kevin and I together. When he died and in the manner in which he did was totally unexpected. Of course I was in shock and my position was that I can’t continue, not because I didn’t think that I could do it on my own but because I simply did not want to do it without Kevin. For the next few years I was in mourning. I’m still in mourning. He was my closest friend. That’s why I made the statement that it was over. It was honest and although I was grieving I still stand by it. What happened as time continued I came to the realization that not only did I miss Kevin, but I missed what had been a huge portion of my life for so many years. I longed to play those Quiet Riot songs, on the road, in front of an audience. I had done that for nearly three decades. I have always had a great relationship with Kevin’s mother. She’s like a second mom to me. My position was that if she had any reservations with me doing anything with the band I would not pursue it any longer. I got together with her and she reminded me that after we buried Kevin and were having a family dinner she had told me that I had to continue the band because Quiet Riot represented Kevin and me. I had no recollection of that conversation I could not believe that we had to say goodbye to my best friend. I always said that Kevin lived his life larger than anyone else including me which is what makes his untimely death even more tragic. No one loved music and rock and roll more than he did. In fact I firmly believe that the person who is most surprised about his death is Kevin himself.

MA: You’ve certainly managed to keep the band alive and even thrive. Of course you’re reviving the classics but does Quiet Riot have any new material coming out?

FB: Yes. We are currently recording the vocals for a new album. We’ve just brought to the Quiet Riot family a fantastic singer named James Durban. He was on Season 10 of American Idol. I think he was fourth from the top before he was passed over. James Durbin is not only an amazing singer, but he is more importantly, an amazing person. Of course he is much younger than the rest of us but you wouldn’t know it by how much he loves rock and roll, specifically heavy metal. We are in the studio in between shows and once the vocals are completed I will go in and make sure the mixes are done. Then I will deliver it to the label so it should come out sometime in the summer.

MA: The people that I have talked to who saw you guys the other night were all impressed with James.

FB: The interesting thing is that he is as tall as Kevin. They are both about 6’4” which gives him a huge presence on the stage. He also has the same energy that Kevin had and his vocal range is ridiculous. We are very fortunate to have him.

MA: Our last question is going to be a hard one. What album or song from your entire career personifies you the most?

FB: Wow that is hard. There are so many songs that I am proud of. I really don’t think I’ve managed to do that just yet but if I had to choose one song from my past I would probably say “Metal Health.” I think that track is a perfect example of what Quiet Riot does. It also personifies what I do within the band. It has to be powerful but it also has to be in control. It needs to have solid time and no drum fills just for the sake of doing them. That song requires the drummer to be very conscious of what is going on around him. If you do it right you come across as being solid and supportive of the players around you. That includes the drum part for that song, the sound of the drums, where I played and where I didn’t play. That track is the definitive Quiet Riot song. It is the last song we play every night.

MA: That’s a great pick.

FB: I’m proud of all of our songs. I’ve never phoned in a gig ever in my life. It’s not just in my older age but I was like this when I was young. You never know if the next time you sit behind the drums it will be your last. I work hard to make every single performance count. My work ethic has so much to do with it. On the desk in my office I have a single dollar bill in a frame that is from the very first show that I ever got paid for. I was fourteen years-old and I was in a band called “A Pound of Flesh.” We played at a Catholic Church social in Queens and we each made thirteen dollars apiece. The first dollar that hit my hand went straight into my pocket. The leftover twelve went in to the other one. The next day I bought this cheap little frame and I pasted the bill inside. I did this because I saw the owner do the same thing in the corner Italian deli. To me that was the mark of being a professional musician. To this day, that one dollar reminds me that hard work pays off and to never take anything for granted. It also reminds me to always move forward whether it’s with small steps or big steps. If you live by that philosophy you’ll definitely go places.

For more information visit:

Frankie Banali website: http://www.frankiebanali.net/

Official Quiet Riot website: https://www.quietriot.band/

DVD: Well Now You’re Here There’s No Way Back: http://www.quietriotmovie.com/get-the-dvd/

Frankie Banali Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/frankiebanali

Frankie Banali You Tube: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=Frankie+Banali

Frankie Banali Twitter: https://twitter.com/FrankieBanali

Current Photo: Joe Tamel

Archive Photo: Sam Emerson